Grape Glossary

Except in Champagne, Pinot Noir is not blended with other grapes. As a component in that blend, it contributes body, texture and aroma. On its own, Pinot Noir is a supple, silkywine that is relatively light in color. It is often called the most sensuous of wines. In New World versions, rich fruit dominates compared with Burgundy’s more austere, subtle elegance.

Pinot Noir is genetically highly unstable, and has mutated to more than 1,000 clones in Burgundy alone. It is susceptible to heat damage as well as to frost, humidity and rot. Difficult and fragile, Pinot buds and ripens early, requiring a cool climate in order to hang on the vine long enough to develop flavor, aroma and complexity. It is moderately vigorous and low in productivity.

The best soil profile for Pinot Noir is well drained, chalky clay, but it also does well in marly loam. There is a mineral in Burgundy called montmorillonite that facilitates the plant’s absorption of elements from the soil. This may be one of the reasons red Burgundies so precisely reflect their terroir.

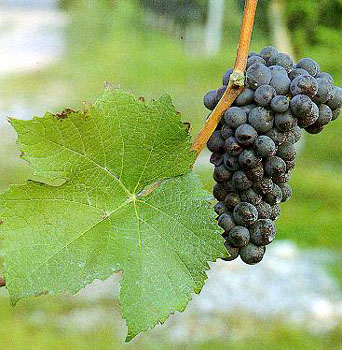

The vine bears small, compact clusters of thin skinned berries that are high in acid, moderate in tannin and color and delicately scented.

Pinot Noir was found in Burgundy when the Romans invaded Gaul and was among the first vines to be domesticated. The name Pinot, which comes from its pinecone shaped clusters, dates to the fourth century. Its prominence as the grape of the Côte d’Or dates to 1395, when plantings of Gamay were banned in favor of Pinot Noir. The red wines of Burgundy are among the costliest and most sought after Pinot Noirs in the world. An original Pinot prototype and an obscure vine called Gouais Blanc are the parents of Pinot Noir and 15 other French varieties, including Chardonnay and Gamay Noir.

Pinot Noir has migrated from France to cool climates around the world, including California, New Zealand and Patagonia in Argentina.